Download the presentation of this section.

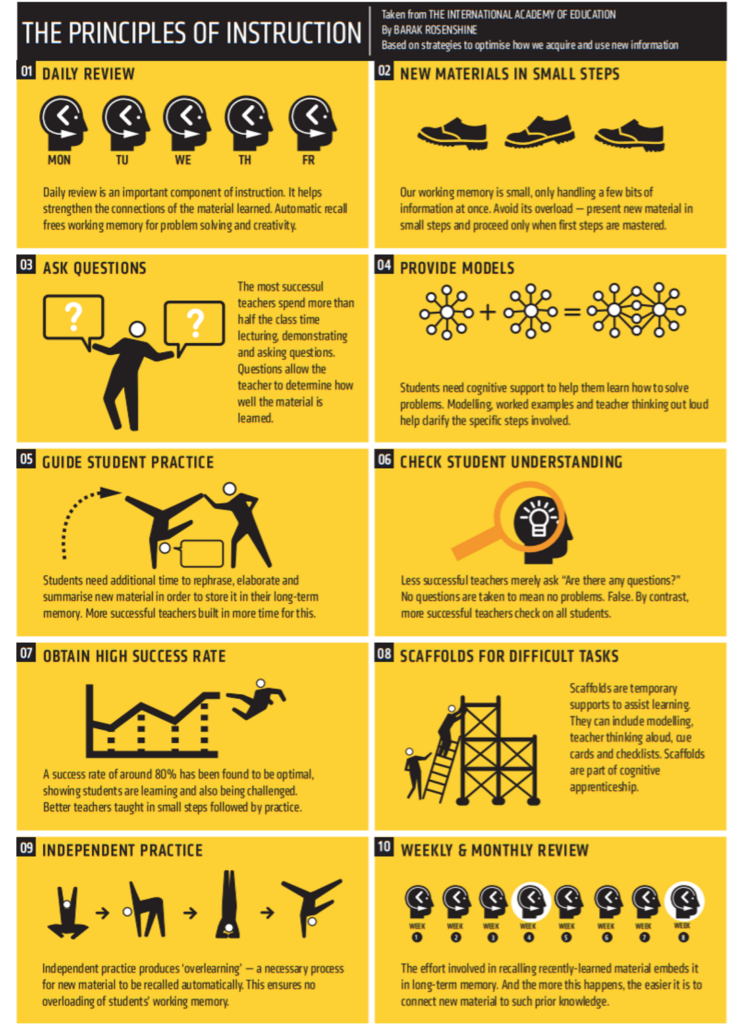

One of the the most popular ways of putting Cognitive Load Theory into to practice are the Rosenshine’s Principles of Instruction. Barack Rosenshine came up with these principles years ago to distill some of the key points of Cognitive Load Theory and to link it with what would have been observed to be the most effective teaching.

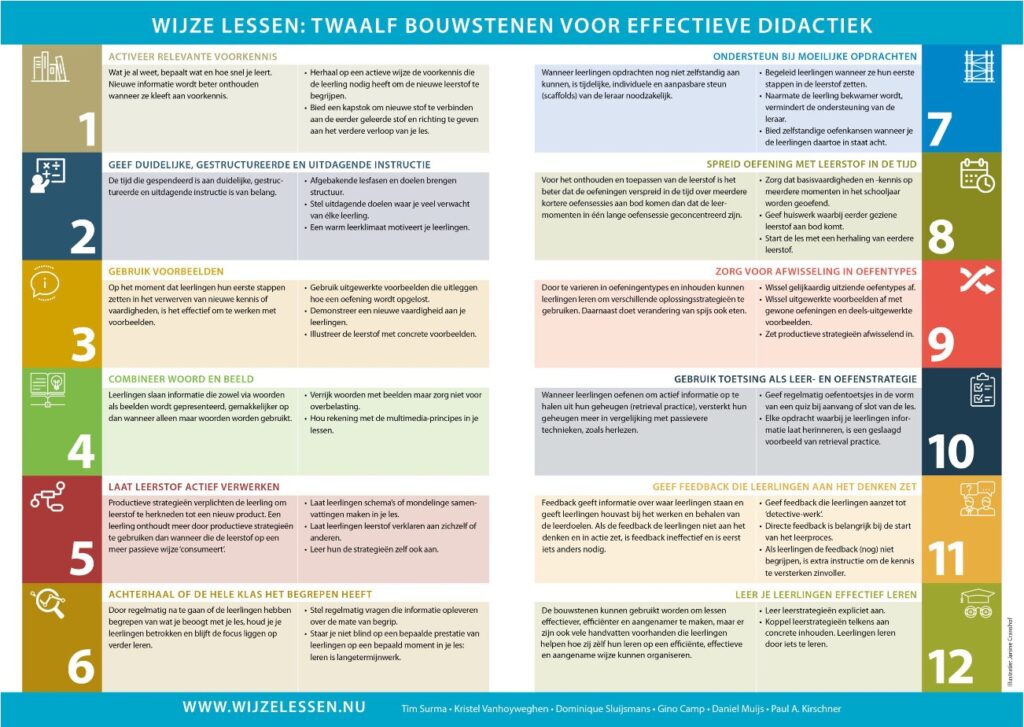

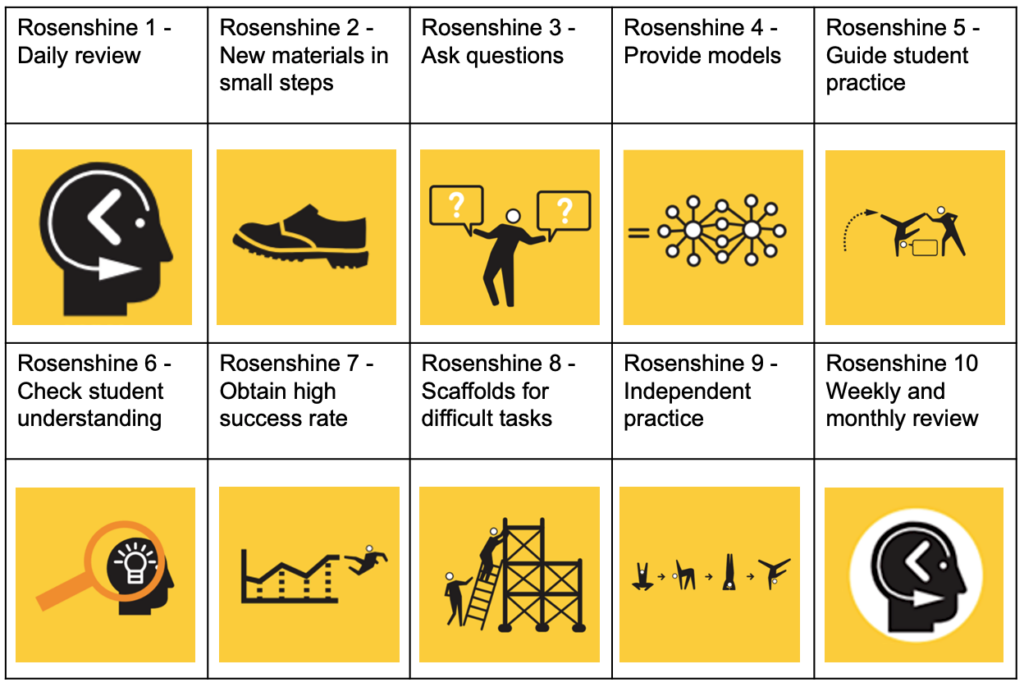

It’s portrayed in this very helpful poster created by an educationalist called Oliver Caviglioli and what he’s done is put the 10 elements into kind of cartoon images or icon images which we can look at more closely in a moment.

It’s portrayed in this very helpful poster created by an educationalist called Oliver Caviglioli and what he’s done is put the 10 elements into kind of cartoon images or icon images which we can look at more closely in a moment.

Just a few key points to start off with – it does bring out this idea of how we connect what we understand in new information (what we’ve learned now with our working memory) to existing comments or ‘schema’. That’s key to the whole idea.

It also introduces us to the idea of ‘novice’ and ‘expert’ the idea that teachers are the experts and our students are to some extent or to a greater extent going to be novices.

So, how we going to get them from being novices towards being experts? We have to share models with them; we have to scaffold the learning; we have to break it down into chunks. And then we have to enable them to practice what they’ve learned. So one key idea there that is that using retrieval practice to build schematic strength but also ‘deliberate practice’ to make sure that the skills and schema are properly embedded.

The ten principles in detail

The idea isn’t that you would try and do all of these things in all of your lessons – there’s no point in considering this to be a sort of slavish model that we have to ad here to, but it’s very important we consider how we use these elements for quite a bit of the time from various stages of the learning process. So, for example when we’re sharing new material, are we sharing it in lots of small chunks or steps? Are we asking plenty of questions to make sure students are really understanding what they’ve learned? Are providing coherent models for them to follow?

Let’s first recap Rosenshine’s ten principles. Below is the name Sherrington gives to each principle, followed by the way Rosenshine expresses each principle in ‘Principles of Instruction’ (all page references are to that article):

- Daily review

‘Begin each lesson with a short review of previous learning: Daily review can strengthen previous learning and can lead to fluent recall’ (p. 13).

- Present new material using small steps

‘Present new material in small steps with student practice after each step: Only present small amounts of new material at any time, and then assist students as they practice this material’ (p. 13).

- Ask questions

‘Ask a large number of questions and check the responses of all students: Questions help students practice new information and connect new material to their prior learning’ (p. 14).

- Provide models

‘Providing students with models and worked examples can help them learn to solve problems faster’ (p. 15).

- Guide student practice

‘Successful teachers spend more time guiding students’ practice of new material’ (p. 16).

- Check for student understanding

‘Checking for student understanding at each point can help students learn the material with fewer errors’ (p. 16).

- Obtain a high success rate

‘It is important for students to achieve a high success rate during classroom instruction’ (p. 17).

- Provide scaffolds for difficult tasks

‘The teacher provides students with temporary supports and scaffolds to assist them when they learn difficult tasks’ (p. 18).

- Independent practice

‘Require and monitor independent practice: Students need extensive, successful, independent practice in order for skills and knowledge to become automatic’ (p. 18).

- Weekly and monthly review

‘Engage students in weekly and monthly review: Students need to be involved in extensive practice in order to develop well-connected and automatic knowledge’ (p. 19).

Expert and novice

Let’s look at a couple of examples of this notion of expert and novice.

Here’s one where the expert is possibly struggling to teach the student. I think it’s a father and son.

The poor little lad is really trying desperately to do what his dad’s doing but his dad is clearly an expert and the child is clearly very very much a novice and doesn’t have the schema in place to be able to know what to do in order to build to the skill of doing the cartwheel. So we can see that happening to be honest we’ve all … suffered from this in our teaching you know try to show students .how to do something and they just can’t manage it because they haven’t got the schema in place. So we need to think about how to step the explanation of what to do. We need to make sure they could experience and practice of lots of lots of steps which for this child would obviously be a few years down the line.

So for a novice structure and guidance are essential. Look at how this person is helping and learning the puppy to get off the stairs. We added the icon images to indicate which Rosenshine principle the person is using.

Building blocks for effective didactics

The idea and concept of Rosenhine is not the only one. the Centre of Expertise for Effective Education of Thomas Moore University College in Belgium e.g. has translated the Cognitive Load Theory with the Rosenhine Principles into 12 building blocks for effective didactics.